The 400 Blows — fences & flight

François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows is built on the idea that a life can be quietly derailed by a chain of misunderstandings rather than by any single act of cruelty. The film’s narrative begins with what appears to be a minor incident in the classroom: a shared photograph passed around, a moment of bad luck in which Antoine happens to be the one the teacher notices. This moment sets off a precise causal chain of punishment, resentment, and escalation. What is crucial is that the system does not act out of malice, but out of rigidity. Authority reacts, misreads, and compounds its own mistakes. The film’s tragedy is structural rather than personal.

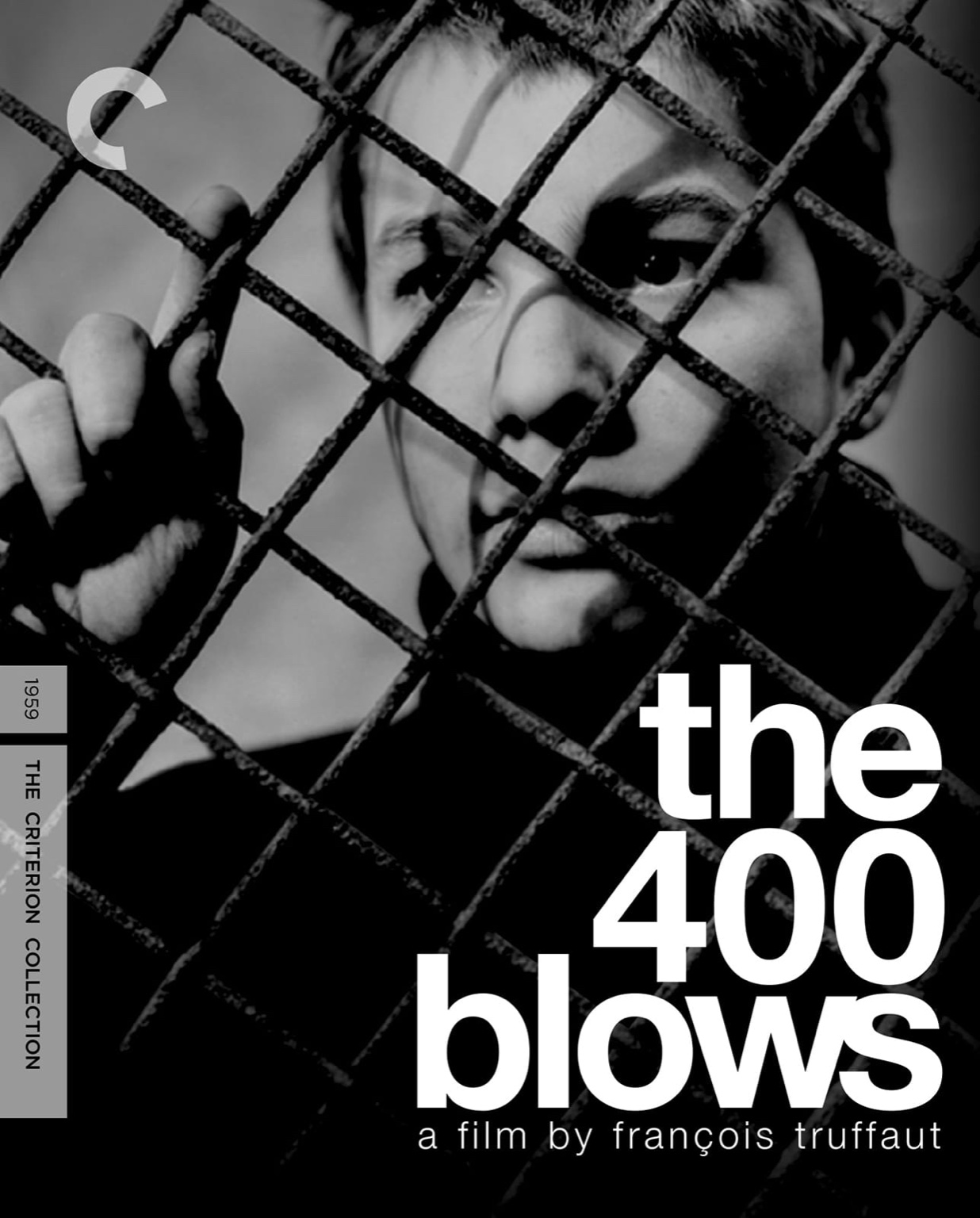

Visually, Truffaut reinforces this through the recurring motif of barriers and fences. Antoine is repeatedly framed behind railings, grids, or confined spaces, long before he ever reaches an actual detention center. The home is cramped and emotionally restrictive, the school imposes moral judgment, and eventually the juvenile facility literalizes what was already present symbolically. The movement from metaphorical enclosure to physical imprisonment feels inevitable rather than shocking. By the time Antoine is locked behind real bars, the audience has already internalized the logic that placed him there.

One of the film’s most revealing moments occurs in the overhead tracking shot of schoolchildren following their gym teacher through the streets of Paris. Seen from above, the children walk in a neat line, but slowly and playfully peel away, drifting off into games and distractions. The teacher continues forward, unaware that nearly everyone has disappeared. The scene is light, funny, and gently absurd, yet quietly devastating. The choice of a high-angle shot is essential. Filmed this way, the sequence becomes abstract and observational rather than dramatic. If shot from eye level with conventional cutting, it might have turned into a moral lesson or a conventional comedy beat. Instead, Truffaut allows the image to suggest how social order dissolves naturally when it fails to recognize individual impulse. Authority moves forward blindly while childhood slips away in all directions.

This balance between warmth and seriousness defines the film’s tone. Although The 400 Blows deals with neglect, alienation, and institutional failure, it never presents childhood as purely tragic. Truffaut understands that a child’s world is filled with curiosity, humor, and play even under pressure. This is reflected in the supporting characters. The harsh first teacher is counterbalanced by the English teacher, whose demeanor and speech bring levity into the classroom. Antoine’s stepfather, while flawed, is often playful and oddly sympathetic. These moments of humor are not distractions but structural necessities. They prevent the film from collapsing into despair and allow the audience to remain emotionally connected rather than overwhelmed.

Near the end, the film introduces a more explicit psychological explanation through Antoine’s conversation with the therapist, revealing painful details about his family background and emotional abandonment. While these revelations deepen the darkness of his situation, they also feel more direct than the rest of the film’s storytelling. By this point, Antoine’s inner life and alienation have already been communicated through behavior, movement, and framing. The added information clarifies rather than transforms our understanding. One could argue the film would still function fully without this verbal confirmation, relying instead on what has already been shown.

The final sequence on the beach brings all of these ideas into focus. Antoine escapes the institution and reaches the sea, a space that initially appears to promise freedom. Yet the ocean immediately becomes another boundary. There is nowhere left to go. When Antoine turns toward the camera, breaking the fourth wall, the film makes its boldest gesture. His gaze implicates the viewer, but it also acknowledges a limit. Even cinema cannot fully liberate him. The freeze-frame and the word “FIN” placed over his face reinforce this tension. Antoine has escaped society’s institutions, but he remains trapped within the frame of representation itself.

In this way, The 400 Blows is not only a film about a misunderstood child, but also a reflection on the limits of social systems, storytelling, and cinematic freedom. Truffaut offers neither resolution nor moral closure. Instead, he leaves us suspended between empathy and distance, reminding us that some lives cannot be fully explained, only observed.